A few months back I was invited by Issues in Science and Technology to write a response to The Real Returns on NIH’s Intramural Research | Real Numbers by Jeffrey Alexander and Rossana Zetina-Beale. The reply was published on December 16th, and - no surprises here given my previous article for the Good Science Project - the basic premise is that NIH Intramural Research Program (IRP) data represents an additional return on taxpayer investment. In that reply, I initially wanted to explore some of the incredible data assets that the NIH’s IRP held that are not made accessible to the outside world by citing a few open access papers that make use of those data assets.

Restricting access to data is not a paywall problem for the NIH IRP (it's an entirely different problem that the NIH should address). However, restricting access to publicly funded research articles that use those data is a paywall problem. For my Issues piece, I wanted to highlight a published example from the Biomedical Translational Research Informatics (BTRIS) data. Largely consisting of clinical research data from hundreds of IRP clinical trials, the BTRIS facilitates linkages across trials and patients that enhance discovery but is only available to IRP researchers. In one innovative reuse of the BTRIS data, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) researchers found candidate drugs for the treatment of glioblastoma, a type of brain tumor, by mining the data using machine learning techniques. IRP researchers have privileged access to those data - without extending that access to outside researchers, we'll never know if the study is replicable, whether they missed critical insights, or what other uses these data might have for novel discovery.

I thought the paper was an ideal example for my piece - featuring a closed-access IRP data asset that has immense potential as a public good. Now, I try my best to only cite research papers that are open access to remain consistent with my values of open science and because I was the policy lead on the 2022 OSTP Public Access Memo (Nelson Memo) that requires all research articles resulting from federally-funded research to be made immediately available to the public without embargo.

Since the NIH is a world-leader in making their funded research publicly accessible through PubMed Central (PMC), it should have been easy to access the paper. After all, NIH public access policy explicitly applies to both extramural and intramural research. What’s more is that NIH employees cannot assert any copyright over the work they do in their official capacity (codified under 17 U.S.C. § 105) meaning that research publications are automatically in the public domain.

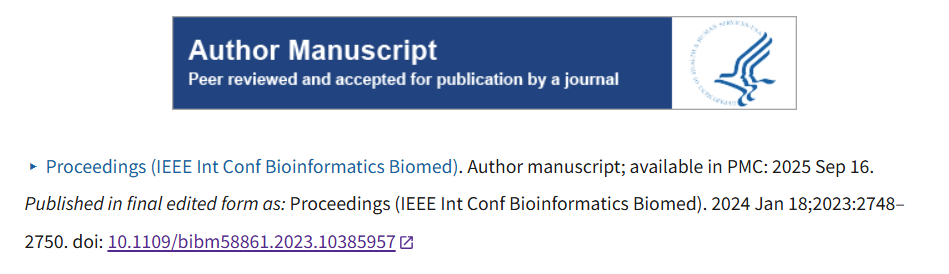

Still, at the time I was preparing my editorial, the paper I wanted to cite was only available behind a paywall and not on PMC. It had been published as a peer-reviewed conference paper in 2023 and still subject to an allowable 12-month embargo ahead of becoming publicly accessible on PMC per the pre-Nelson Memo-era NIH public access policy. Clearly, though, the paper was nonetheless out-of-compliance when I wanted to read and cite it.

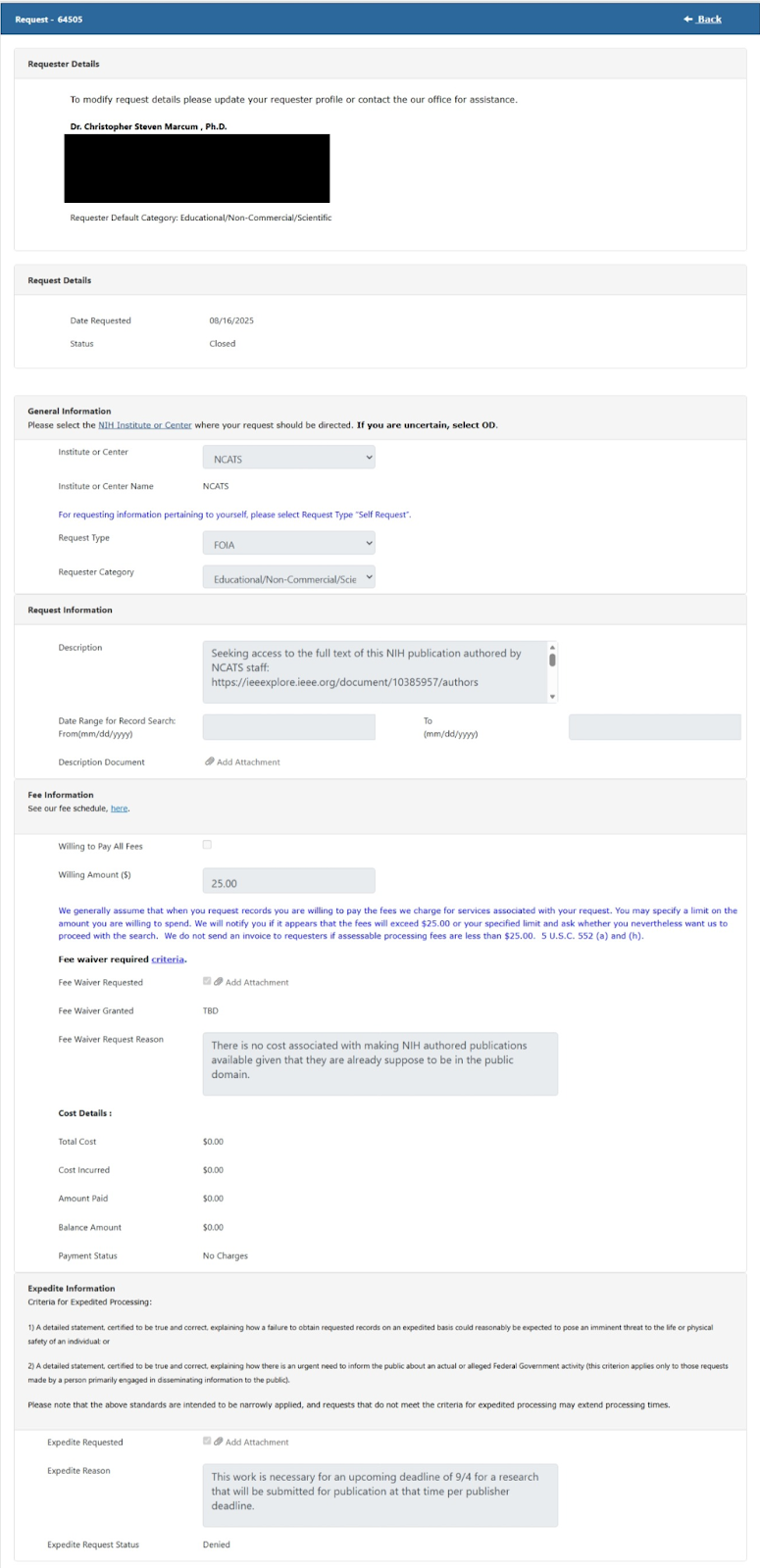

So, how do you gain access to research that should be openly and freely available from the Federal government? In my case, I first reached out to the corresponding author asking for the paper and recommending that it be deposited in PMC to comply with the NIH public access policy. When the author did not reply, I turned to the NIH Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) office.

On August 16th, 2025 I requested access to the paper, noting that it was out of compliance with NIH public access policy and the work would be in the public domain as it was entirely done by federal employees. I explained that I had a deadline in two weeks that I needed the paper for and requested expedited review. It should have been trivial for the NIH FOIA Office to immediately turn around the request - they could have gone to the NIH staff library which has institutional access to the paper in the same day. However, a few days later, I received a message back from the NIH FOIA office indicating that my expedited review request was denied. I was clearly not going to get this paper in time while waiting for NIH FOIA to respond.

Hoping to still get access to the paper through NIH and make my editorial deadline, I then turned to inquiring with the NCATS Director. That should be the official responsible for ensuring that research published by NCATS staff is compliant with NIH policy. Again, no response, and so I ultimately omitted the reference from my Issues piece.

A Few Months Later...

I had put the paper and the FOIA request out-of-mind since my editorial deadline had passed. So, it was with a bit of surprise that - fast forward three-months - NIH FOIA came through and provided me with a PDF of the paper. People familiar with FOIA’ing the NIH will marvel at the speed of that response, especially since the government shutdown occurred during the FOIA review. Despite statutory obligations for 20-day response times, NIH FOIA is woefully understaffed and over-burdened with requests and can sometimes take months to respond to even simple requests. According to data on foia.gov, the NIH had an average response time in 2024 of more than 130 days for simple requests. Yikes.

Ironically, the paper appeared on PMC exactly one month to the day after I submitted my FOIA request, and two months to the day prior to the NIH FOIA office responding to me with the paper.

A Paywall Problem?

What does this experience teach us about public access at NIH? I think there are a few lessons:

First, FOIA should be a last resort and is not an appropriate route to obtain access to federally-funded research data and results. The NIH FOIA staff are really wonderful and do their best under highly constrained conditions; they should not have to waste resources responding to FOIA requests for works that are: 1) already in the public domain and, 2) should be publicly available on PMC under NIH's own policies.

Second, NIH IRP researchers need training on the non-copyrightable nature of their research and should be required to deposit their author-accepted manuscripts in PMC. When I was a newly minted staff scientist in the IRP at the NIH, I cannot recall receiving guidance or training on public access policies. Training IRP researchers to comply with NIH's own policies could be really easy. There are readily available tutorials from the NIH staff library and a nice video from the NLM on the NIH Manuscript Submission System on YouTube.

And third, the NIH Intramural Research Program really should represent the gold standard of public access and be a model for the extramural community. The NIH IRP should be leading by example have 100% compliance with the NIH public access policy. There is no reasonable excuse for a paper authored by NIH IRP researchers to remain behind a paywall, particularly now that the updated and accelerated NIH public access policy requires immediate public access without embargo.

Now, a single case like this obviously does not a paywall problem make. Access to IRP research has, however, been historically limited because of a legacy of paywalls from past policies. Before the original public access policy took root in 2008, there was no requirement for intramural researchers to make their work freely available to the public, so older articles often remain locked behind paywalls. The NIH has never retroactively applied its public access policies but because those articles were written by IRP researchers, they are in the public domain (and would be subject to disclosure under FOIA).

Even more recently published IRP research faces temporary roadblocks to full public access. Because the latest zero-embargo policy only went into effect in July of 2025, articles published shortly before that date are still operating under the old policy that allowed for the publisher to embargo their version from public release. This means a paper published in early 2025 could currently be in its "embargo period," allowing the publisher to keep it private for up to 12 months before NIH opens it up to the public via PMC.

The NIH requires author accepted manuscripts be deposited into PubMed Central (PMC), the agency's "designated repository" per the Nelson Memo. Thus, finding an article free to read (e.g., as open-access) on a journal's website doesn't necessarily mean the paper is in compliance with the NIH policy. More than 2,000 articles published between 2022 and 2026 associated with IRP researchers appear in PubMed (PubMed is like PMC’s card catalog cousin, providing indexing information about articles without the full-text) but have no entry in PubMed Central. An extensive selection of such articles can be found in a repository on my github, along with code to collect information about articles associated with IRP researchers from PubMed.

Some of these papers are free to read on the publisher’s website, such as The NIH-led research response to COVID-19. Some others are locked behind paywalls, like Structure–Activity Relationships of Antibody-Drug Conjugates: A Systematic Review of Chemistry on the Trastuzumab Scaffold. And still others are locked behind paywalls despite PubMed indicating that there is free full-text available on the publisher site, like with The role of HIV as a risk modifier for coronary endothelial function in young adults. Most of these IRP papers will eventually become deposited into PMC, albeit on timelines that may not always align with policy.

To ensure compliance the NIH should require that, after sufficient training, intramural researchers deposit their author-accepted manuscripts directly into PMC the moment they are accepted for publication. While it is tempting to rely on publishers to handle this process, third-party deposits can fail or otherwise become delayed. By mandating that researchers upload their own final, peer-reviewed text immediately, the NIH ensures that a copy is secured for public access. This proactive step eliminates confusion over "zero-embargo" timing and guarantees that taxpayer-funded science conducted by IRP researchers is safely preserved in the public domain, regardless of what happens vis-à-vis the publisher site. IRP authors' works cannot be copyrighted, but they can be paywalled, and that is a problem for public access.

References

- Alexander, Jeffrey, and Rossana Zetina-Beale. “The Real Returns on NIH’s Intramural Research.” Issues in Science and Technology 41, no. 4 (Summer 2025): 36–39. https://doi.org/10.58875/YZSL6513/

- Marcum, C. (Fall 2025). “Expand Data Access!” Issues in Science and Technology 42, no. 1. https://issues.org/nih-irb-data-alexander-zetina-beale-forum/

- Marcum, C. S. (January 15th, 2025). "Reforming the NIH’s Intramural Program." The Good Science Project. https://goodscience.substack.com/p/reforming-the-nihs-intramural-program

- 17 U.S. Code § 105 - Subject matter of copyright: United States Government works. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved January 5, 2026, from: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/105

- Marcum, C. S., & Donohue, R. (2022, August 25). Breakthroughs for All: Delivering Equitable Access to America’s Research | OSTP. The White House. Retrieved January 5, 2026, from: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/08/25/breakthroughs-for-alldelivering-equitable-access-to-americas-research/

- White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. (August 25th, 2022). Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies: Ensuring Free, Immediate, and Equitable Access to Federally Funded Research. Retrieved January 5, 2026, from: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/08-2022-OSTP-Public-Access-Memo.pdf

- Sun, S., Tian, Y., & Zhu, Q. (2023). Mining NIH BTRIS Data for Drug Repurposing: A Case Study of Glioblastoma. Proceedings. IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, 2023, 2748–2750. http://10.1109/bibm58861.2023.10385957

- Collins, F., Adam, S., Colvis, C., Desrosiers, E., Draghia-Akli, R., Fauci, A., Freire, M., Gibbons, G., Hall, M., Hughes, E., Jansen, K., Kurilla, M., Lane, H. C., Lowy, D., Marks, P., Menetski, J., Pao, W., Pérez-Stable, E., Purcell, L., … Young, J. (2023). The NIH-led research response to COVID-19. Science, 379(6631), 441–444. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf5167

- Matikonda, S. S., McLaughlin, R., Shrestha, P., Lipshultz, C., & Schnermann, M. J. (2022). Structure–Activity Relationships of Antibody-Drug Conjugates: A Systematic Review of Chemistry on the Trastuzumab Scaffold. Bioconjugate Chemistry, 33(7), 1241–1253. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00177

- Abd‐Elmoniem, K. Z., Yeramosu, T., Purdy, J. B., Ouwerkerk, R., Matta, J. R., Ishaq, H., Hawkins, K., Curl, K., Dee, N., Gharib, A. M., & Hadigan, C. (2023). The role of HIV as a risk modifier for coronary endothelial function in young adults. HIV Medicine, 24(7), 818–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.13484

Copyright © 2026 Christopher Steven Marcum. Distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.