Coming from the Global South, I have frequently experienced the cucaracha (cockroach) syndrome, where I feel like what I do is not interesting. This is the phrase that I give to the feeling of my research and perspective being routinely undervalued and underappreciated due to my local context and language abilities.

When peer reviewers discounted our data from Brazil as worthless, it strengthened that feeling of being undervalued and underappreciated. In this post, I share that story for the first time.

Our research

One of my students interested themselves with the well-being of IT personnel in Brazil. This is an interesting research question, especially in our area, as well-being in the US or Europe is very different from well-being in Brazil. However, most measures are developed with a Western context, not capturing the phenomena as well in our context. I discussed with some colleagues that well-being is different in different cultures, the reference of well-being (public versus private) and the level of analysis (group versus individual) being different.

For example, when asking how happy a person is, you are asking from an individualistic perspective. However, from a collectivist perspective one’s happiness could be judged differently. For example, asking if your group is happy could then mean you too are happy.

We used a measure developed in the Brazilian context, and even though it is nothing special, we used standard methodologies for validation. To ensure interoperability and cross-cultural understanding of our findings, we combined the scale with an international measure (mixed method approach). We submitted the results to a (in our rankings considered second tier) journal, hoping it would be accepted quickly, coherent with our expectations.

What happened, we did not expect, however.

Our experience

During the review process, we ran into several issues. Just to name a few, the reviewers indicated:

- our Portuguese citations were useless

- the Brazilian sample was not interesting at all

- our English was not good enough (on that they probably are right).

Both reviewers said the same, one with kinder words than the other. Nonetheless, I felt put in my place - like I should only read and learn from English citations, from Western samples, and highly proficient English speakers.

The outcome

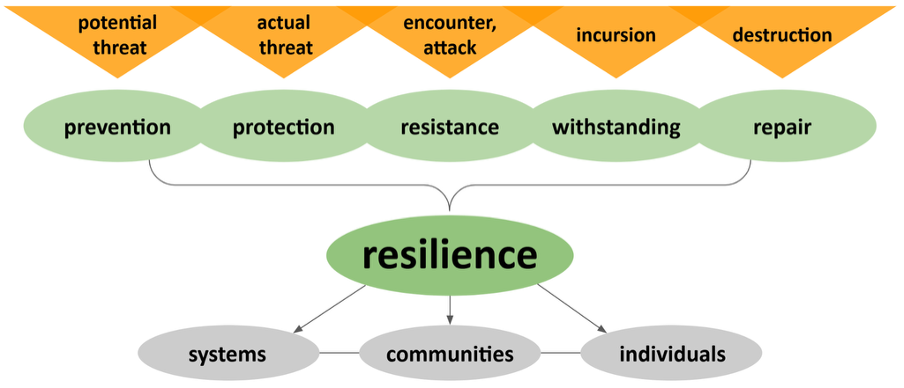

The important point of the story: social science bias (sample, measures, perspectives and authors) is real. Unfortunately, it is just one example. I am not the only one. Cockroaches are resistant to radiation, but not to being stepped on.

I am not a cucaracha, and yet I felt treated like one.

How can we know whether this happens once or many times? Nobody's work needs to be discounted because of their language, their heritage, or their topic. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines state that diversity and inclusivity require non-discriminatory practices to be implemented, and our story highlights that these guidelines still need to be implemented into the everyday reviews and processes at publishers.

Copyright © 2023 Amalia Raquel Pérez-Nebra. Distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.