The increasingly hostile attitude of the new U.S. government towards science and academia leaves many of us deeply concerned— if not outright alarmed. In an effort to better understand the unfolding situation and navigate its potential impacts, we provide an overview of five types of threats, each supported by links to documented sources. We also propose a simple resilience framework and use it to interpret the multitude of actions of many different stakeholders that help to counter the threats and attacks. Finally, we explore the particular case of open science: does its openness make it more susceptible to these threats, or could it, in fact, be a source of greater resilience?

Under threat

Only 100 days after the installation of the Trump administration, we’ve seen an unprecedented attack on the geopolitical and financial world order, on gender, equality, and inclusion agendas, civil rights, and science and scientists. Well-meant, kind advice from Nature editors to keep building policies on sound scientific knowledge was fully ignored by the incoming U.S. president. This poses serious challenges for open science, especially when combined with worries over AI, big tech dependence, and austerity and funding cuts in many countries (including those in the Netherlands). Of course, science and scientists have been under threat much longer in many countries with authoritarian regimes. But what is happening in the U.S. now is certainly a catalyst to look at the resilience of science globally.

Will open science still be possible? Is open science resilient and able to continue to make science more accessible and engaging, more open to participation and reuse, and more transparent and reproducible? We see challenges in five major areas:

- funding,

- research infrastructure,

- academic freedom,

- safety of members of the academic community and

- disinformation and science scepticism.

It is shocking to witness the daily news of threats and actual damage coming from the U.S., the most influential player in the global science system. We cannot track and list everything here (for that see e.g., Peter Suber’s Mastodon thread also available as plain text overview on Berkman Klein Center website and also see the Action Lab overview of protests and trackers), but it is important to show the diversity of incursions, as they also demand a diverse range of actions and strategies to deal with them. Let's look at some prominent examples that have unfolded over the past 100 days of the current Trump administration.

Recent events

Funding cuts

The U.S. government is cutting funding for research at NSF and NIH, halving budgets for 2026 and cancelling existing grants, some 800 in total. It is also cutting funding for federal agencies like NASA, NOAA, USDA, CDC and USGS, specifically targeting their research and data collecting activities and within that, especially on anything related to diversity, gender, climate, public health and the environment. Leadership is replaced, grants to scientists are terminated because of censored subjects, laboratories are defunded, and international scientific collaboration is hampered. All of these are not orderly restructuring of the science apparatus, but unprecedented destruction akin to using a wrecking ball. And these are not merely austerity measures, but targeted cuts affecting certain types of research specifically and as such also affecting academic freedom. The Trump administration has also halted funding to many big universities, amounting to many billions of dollars withheld. The same holds for the almost entire defunding of the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), even after the latter had in February agreed to promptly comply with all executive orders of the Trump administration. IMLS funds many projects and services, including some related to open science, such as the Open Grants database. And in the new 2026 budget request sent to the US Congress, all federal agencies involved in science, including NIH, NSF, NASA, and CDC, are seeing severe budget cuts, usually way above the average non-defence cuts. While these U.S. cuts are severe, they are not unique. The Netherlands, for instance, also faces a significant reduction in government R&D spending.

Research infrastructure

In the wake of all the attacks on science, research infrastructure is directly affected or eradicated because it was supplied by a federal agency. Or it is indirectly threatened when it depends on federal funding or tax-exempt status. It concerns data and software as well as platforms and repositories. It can take the form of changes in the governance, downsizing, changing inclusion criteria or even more frightening: entire eradication. Some federal organisations, like NOAA, are publishing lists of databases that will be retired or put on hold. The immediate halting of all current NEH grants poses severe problems for the Knowledge Commons network and platform. An analysis by Invest in Open Infrastructure indicated that at least seven important infrastructures (partly) depend on federal grants, totalling nearly 12 million USD. Publication databases are threatened, such as the education research database ERIC, which may have to shrink or close because of funding cuts. There are also libraries of federal agencies, such as the U.S. Naval Academy, that had to remove 100s of books on targeted topics, and it is likely similar things are happening at other agencies. We also see intimidation of Wikipedia and Wikimedia, one of the tools in the researcher toolbox, over editorial policies and ‘foreign influence’. The U.S. government could revoke its tax-exempt (‘501(c)(3)’) status. Related but of a different origin is the heavy burden AI scraping puts on especially open repositories, as reported by REpEc, Wikimedia and OAPEN, among many.

In the early weeks of the new U.S. administration we also saw some organisations, such as societies or advocacy organisations, remove or change DEI-related wordings from their website, even before receiving any request to do so. In later stages some apologised and reconfirmed their support for inclusion while others perhaps chose to continue to work on fostering DEI silently.

Yet another U.S. government attack on resources is the actual taking down of selected individual publications. This is scary because it is hard to track down. In the wake of all this, open science and its related infrastructure and communities are also suddenly subject to these policies. Not least because several open science principles (e.g., transparency and accountability, inclusion and diversity, etc.) do not fit in with the current Trump administration’s vision at all.

Academic freedom

Threatening and limiting academic freedom is perhaps the most fundamental of incursions in academia. This happens where academics are told what and how to teach and research. In the U.S., currently, this is happening when federal funds are withheld to force institutions to adjust their governance to fit with the ideology of the U.S. government. This first became clear with Columbia University, and later with many more, most notably Harvard, which gave insight into the process by publishing the letters they received from and sent to the U.S. Department of Education. On top of this, there is now an executive order to overhaul the university accreditation system. Needless to say, very selectively slashing federal research agencies and their grant programmes, while not an intrusion of academic freedom per se, of course, has effects that add to those of direct intervention.

Another very clear intrusion of academic freedom is lists with forbidden terminology. The administration compiled lists of words banned from websites and used to flag research grant proposals, and some departments go even further with additional measures, such as the USDA, even preformatting the lists of banned terms as a giant Boolean query, making it easy to check documents. Of course, even when used to target research and researchers in federal agencies, this can be seen as limiting academic freedom. It is important to note that these term lists are not new. The CDC already received such a list with forbidden words at the beginning of Trump's first term. Even AI research is affected, as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) ditches terms like ‘AI safety’ and ‘responsible AI’ from required skills descriptions. There is even a link to AI in the firing of the Director of the U.S. Copyright Office shortly after removing the Librarian of Congress from her office.

Yet another example threatening academic freedom is the intimidating letters received by scientists in Australia, The Netherlands and other countries who are participating in projects with USGS and other U.S. agencies. Finally, yet another very clear intrusion is also happening: approaching individual journals to ask intimidating questions about editorial policies. And the U.S. government even targets Harvard Law Review over presumed discriminatory manuscript selection. Still other orders and new policies infringing academic freedom that we now see in the U.S. are those limiting or halting the ability of researchers to travel abroad or to collaborate with researchers abroad. Again, here it is important to note that the inability to travel, travel visa-free or get a visa (especially for rich Western countries) has been a hard reality for researchers from many countries in the Global South for decades.

Safety of members of academic communities

Over the past few months, we have also seen increasing worries about the safety of members of the academic community. The widely reported cases of Mahmoud Khalil and Rümeysa Öztürk have shocked many. With 1000s of visas of foreign-born students being revoked and with these cases of students being seized from the street and academics intimidated and having their laptops examined at the border or even being detained, it is clear that the U.S. government instils fear among members of the academic community, in the U.S. itself and abroad. Because of this, scientists internationally are rethinking U.S. conference attendance, and students fear traveling. Especially border checks involving security personnel requiring access to mobile phones and laptops have a chilling effect. Another very clear form of governmental overreach threatening the freedom of researchers is the regulation that NIH-grantees cannot engage in DEI or boycotts. As part of the Trump government order to only recognise two biological sexes, and institutions choosing to preemptively comply and change their policies, there are now serious fears that university campuses will become less welcoming to transgender and non-binary community members. What's really scary about this all is the total unpredictability of it.

Disinformation and science scepticism

Lastly, in this context, disinformation and science scepticism, whether in social media or the political arena, are only fueled further. Science scepticism has proliferated so far that prominent scientists are now talking of ‘science under siege’ in a forthcoming book. Disinformation and science scepticism are two intertwined problems that pose serious challenges to society, especially in the context of public health, climate change, and technological developments such as AI. Disinformation campaigns often target scientific institutions, casting doubt on scientists, methods or resources, and we see this develop further when governments actively support these campaigns. The current U.S. government actively reduces measures to counter disinformation, cancelling research grants on the topic and enticing big tech to cease moderation. There are even efforts to force other countries to do the same.

Resilience model

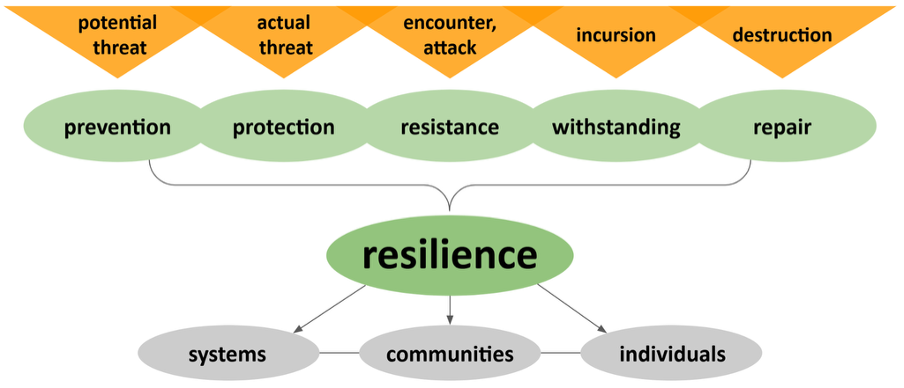

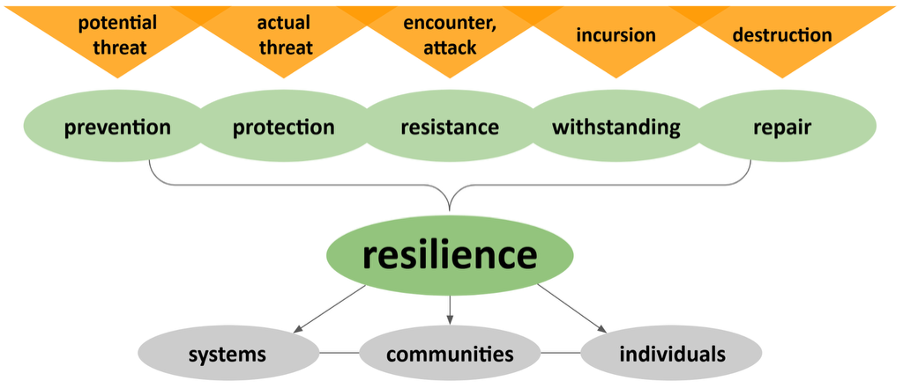

The concept of ‘resilient’ (open) science helps assess what mechanisms or arrangements are in place to safeguard the way we work. One could discern between five types of threat or incursions (the orange triangles in the image), that in some cases also describe phases in a process, from just a potential threat to actual destruction of some of what we have, are or use. The types of resilience against each of those threats range from ‘prevention’ to eventual ‘protection’, and via ‘resistance’ and ‘withstanding’ to ‘repair’.

Of course, ideally, all potential threats do not occur or are successfully prevented because there is mutual interest, or through arrangements such as a social contract with society, as we have with academic freedom and long-term funding agreements. Continuous action to retain trust and support in science also contributes to prevention. Some actual threats can be warded off with physical or technical protection; an example of something simple to execute would be using 2-factor authentication against digital break-ins. To be able to protect our way of working, it will often be crucial to have (digital) sovereignty and control, especially regarding our online infrastructures. When, despite prevention and protection, there is an actual unfriendly encounter or ‘attack’, resistance in the form of protest or legal action can help, especially when that is based on solidarity in the community. If this all fails and an incursion of whatever form takes place, resilient communities or organisations may withstand that and bounce back, given sufficient resources and flexibility. When even that fails and actual destruction is taking place, creativity, expertise and a ‘make-do mentality’ are needed to repair the damage already done or to find workarounds. A similar multi-level and multi-phase approach to resilience has been detailed recently in Protecting Science in Times of Crisis, a timely report by the International Science Council.

Using these concepts of different types of threats and aspects of resilience helps understand real-world examples of the five challenges that we identified in the opening of this post.

Resilience in practice

Funding

If funding is reduced or falls away, like we are witnessing in the Netherlands, the U.S. and many other countries, and challenging that funding cut is not successful, it is hard to avoid painful measures. It is, however, important to clearly voice opposition against governmental overreach, preferably in a coordinated way, like over 500 U.S. institutions now do, collaboratively. Harvard also takes the next step, legal action, while they do seem to bend on some other issues, given the renaming of their diversity office. Solidarity might help to resist and partially withstand cuts, as some U.S. institutions under the Big Ten umbrella may now be considering in the form of a proposed Mutual Defence Compact. Scholarly societies have been relatively quiet, with the notable exception of the APA-led early statement from the United Science Alliance signed by some 50 societies in the social sciences and life sciences. And the library community has been vocal, including some very strong statements as well as a lawsuit and a toolkit for organising support. Finally, it is good to see that some research that has been slashed by federal agencies is being taken over by others, such as AGU and AMS societies, trying to fill the gap of the U.S. national climate assessment reports.

While it cannot make up for frozen grants and lay-offs, learning from low-resourced organisations and countries is helpful in thinking about how to continue the core of teaching and research. And open science in particular should be helpful in being able to continue, building on freely available publications, shared resources and open source technology. Providing and using publication models that can operate at lower cost, such as preprint archives, publish-review-curate (PRC) models or diamond journals, can save money, among many other reasons to pursue these.

For U.S. cases where lay-offs are inevitable, resilience on an international scale might offer relief for some individuals. Indeed, many U.S. researchers consider moving to Canada or Europe, especially when funding and open positions are available or organised at institutions abroad, as we see happening. French, German, and Dutch research organisations, funders, as well as universities, have taken initiatives to attract and provide a home for U.S. researchers. Now the EU has also stepped in with a €500M fund to attract scientists. It will remain a solution for a select group, though, and it has provoked debate and resistance, as institutions in some of the countries offering a new home to US researchers are facing their own austerity measures in higher education. Next to these funds and concrete job opportunities, for anyone laid off or under threat thereof, it is important to be recognised. The Silenced Science Stories initiative does that by presenting stories and artists' visualisations of individual scientists and how they have been affected.

Research infrastructure

When (open) infrastructures and data resources are compromised, reduced in coverage or functionality or entirely removed, resilience would mean that the research communities are able to withstand or repair that. Ideally, there is redundancy in the form of mirrors and copies, open source code, or comparable alternative systems (e.g. alternatives for PubMed or for preprint and article repositories). But often that redundancy will not be in place because the infrastructure or resource was simply trusted, being in a large democracy and enjoying structural funding. That will mean the community has to be alert (e.g. through this service status tracker for important U.S. biomedical data infrastructures) and try to save or repair. In terms of data and websites, we see that indeed organisations (for example, the Data Rescue Project with their public list of datasets and databases that have been copied, but also the Public Environmental Data Partners with their list of saved data). In Europe, Pangaea has offered to help. There are also many individuals (for example, here and here) setting up all kinds of actions to safeguard data, with the onslaught on these resources by the Trump administration. The Library, Archive & Open Research Services blog provides an excellent and updated overview of alternative sources available or newly created. The process can be astonishingly fast, like the rescue operation for the 500K full-text documents in the ERIC database mentioned, which are now available via ERICA. The Dutch stakeholders are also planning to take a role, trying to ensure continued data availability for researchers in the Netherlands when access to data on U.S. servers is no longer guaranteed, and in some cases, researchers are already taking actions (in the shadows). As an example of flexibility, we see that for new and ongoing (collaborative) projects, some universities now advise researchers to store data on internal or non-U.S. servers, especially for topics that are targeted in the U.S.. Peter Suber advises anyone to deposit copies of articles and data currently in U.S. federally managed repositories in non-government-related repositories. And people at Knowledge Commons plan to build a digital preservation network that will be free from any government’s interference. Again, data, archives and libraries are not only under threat in the U.S.. We need to address the safety of data around the world. It is good to recognise that resilience actions around resources need not all be large or coordinated to be stimulating, as the Operation Caged Bird, in which a small Maryland bookshop now provides copies of the books removed from the Naval Academy library.

Even if the necessary redundancy of infrastructure is in place, there will often be issues in getting that to work or getting it to scale, such as making sure that a tool like EuropePMC can function as a full alternative for PubMed, which might be under threat. ZB Med, the German information centre for life sciences, has taken steps to produce and maintain a copy of PubMed. Repair can also take the form of finding alternative funding to maintain these resources, through crowdsourcing and donations or collaboration with institutions anywhere that show solidarity. Looking forward, there are some pleas to take steps to structurally move away from nationally managed infrastructure. On the code and software front, some are taking steps to move away from platforms under U.S. jurisdiction and move their repositories from GitHub to the German Codeberg platform. In Europe, many Higher Education organisations and governments are now stepping up existing efforts to move away or at least reconsider their strong dependence on U.S. big tech and improve digital sovereignty, often spurred by their own staff. European and/or open-source solutions for all kinds of domains and applications are getting more exposure. French (Mistral, Doc, Cryptpad) and German (NextCloud, Codeberg, Ecosia, Mastodon) organisations, especially, are becoming better known as providers of software and platform alternatives. Having an alternative to move to when things go wrong is a crucial part of resilience for open science. Finally, it is good to see there is growing awareness of the importance of safeguarding globally collaborative or networked websites and services, such as Wikimedia’s Wikipedia and Wikidata, the Internet Archive and its Wayback Machine, and registries such as ORCID and Crossref, all incorporated under U.S. law.

Academic freedom

For challenges to academic freedom, resistance in the form of a strong public stance (such as the statement by Harvard), legal action, fostering public and political awareness, and small and big protests are all happening. Making sure that the value of independent scholarship and independent academic institutions is broadly supported is paramount, but it is difficult to achieve that in the short term once trust has waned. A crucial but often forgotten element of successful resistance is calling out incursions for what they are. After initial bending and complying, some U.S. universities and scholars are now taking a clearer stance, calling out antisemitism allegations and allegations over lack of viewpoint diversity for what they are: pretexts to reign in the role of academia (probably phrased best by Timothy Snyder). Some highly visible journals are now taking a stronger stance, like The Lancet recently did. The community of scientific editors has published a statement on external influence on editorial decisions, and they have created resources on editorial independence and how to deal with banned terms lists and censorship. Also, collaborative shouting out against censorship is happening. It is good and not surprising to see people involved (4401 individuals at the time of writing) in the openness of research to have drafted the Declaration to #DefendResearch against U.S. government censorship.

Safety of members of academic communities

Cases where the safety of individual scholars or students is compromised or under threat are extremely sensitive and complex. Depending on the situation, various resilience strategies may offer partial or temporary solutions: protection (helping with privacy and data safety), resistance (legal support, public shout outs, shows of solidarity) withstanding (not travelling but using online options), or repair (offering affected people jobs outside the area of threat). Legal action is most important and can still have an effect, as was shown by the revocation of student visas. While some institutions are still hesitant to do this, some individuals already go so far as to provide a ‘safety manual’ for academics visiting the U.S. WIRED has written a guide on how to protect sensitive data on your phone when you fear it could be searched by customs staff. And, meanwhile, many conference organising organisations are reconsidering their venue choice or taking measures to better facilitate virtual attendance at conferences, helping to avoid unsafe travel. It does require flexibility and a ‘make do’ mentality, but experience and technology developed during the COVID years can now be leveraged.

Disinformation and science scepticism

Forms of resilience are also important to reduce the effects of disinformation and science scepticism. Disinformation around science, its outcomes and scientists themselves increases the acceptance of attacks on science. It is vital to retain or restore trust, and academia needs to further reflect on how to do that, as was concluded in a recent NWO-organised debate. But to support that process, much can also be done in a more practical sense. Supporting platforms without strong algorithms that foster the spread of disinformation can help. Contact between academics and parliamentary representatives can help. Regulating social media, as the EU does, can also help, just as trying to come up with alternatives for big U.S. genAI chatbots. Concrete support for organisations and individuals being targeted, especially women, people of colour and people identifying as LGBTQ+, is crucial and includes legal, technical and mental support. Without it, open science will lose its promise of inclusion and diversity.

Overall, resilience sometimes involves voicing your opinion clearly and loudly, when that can be done safely. Next to the open letters, statements and legal action, there is also broad support for public action and protest organised by StandUpforScience, among others.

Is Open Science resilience different?

Open science values need to be upheld by the community, especially now, as was argued in a recent Upstream post. For the open science community, it is important to assess its vulnerabilities and its strengths in view of resilience. Open science and research infrastructure cross borders. What does this mean in times of geopolitical unrest or crisis? How will the unpredictable and discriminatory behaviour of the U.S. administration and others with similar approaches affect open science and academia? Overall, open science might be more vulnerable to current threats and incursions because it is more dependent on sharing generally, which is heavily done on vulnerable U.S. commercial platforms. Also, it is more dependent on date/code sharing and international collaborations, which might be reconsidered under geopolitical tensions. Furthermore, open science is more visible and aims at societal impact, often in an inclusive way, making it an easy first target. Finally, open science is strong in fields related to global challenges (climate, epidemics, inequality), making it more vulnerable to science scepticism and targeted attacks.

On the other hand, the open science communities may have more members with a ‘make do’ mentality that can help withstand attacks or help repair damage. Also, some open science practices are relatively low cost, especially when based on open source software, and thus perhaps easier to maintain under austerity. Diamond open-access publications and open textbooks carry the additional advantage of being mostly immune to trade tariffs. The open nature of resources used in open science also renders them easier to fork, mirror, adapt and repair if necessary. But the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Each case is different, and what is possible depends on the specific context. What is clear, though, is that resilience depends on actions of the research community members, organisations, as well as individuals, to make sure safeguards are in place and to take action when people or resources are at risk.

Where next?

Hopefully, from the many examples we have provided in this piece, it becomes clear that we are dealing with a very serious problem and, in some cases, acute challenges and threats. Safeguarding public and academic values of open, transparent, and above all uncensored scientific information for society and communities should not be taken for granted. In light of the current global political situation, we mustn’t be naive and we need to ask ourselves important questions about where and how research infrastructure is governed, hosted, managed and organised, and how this relates to safeguarding academic freedom, academic and public values and (published) results of research.

Concretely, an early conclusion to draw is that well-coordinated, collaborative vocal statements and actions may be more effective than keeping the head low or complying easily, especially in the long term. Also, that it is wise to cherish the grassroots creativity and fast action of individual community members in safeguarding resources. We may need to invest more in solidarity between and within institutions and provide deep support and advice for those most affected. We have to up our game in making infrastructure resilient by steadily building mirrors of databases and repositories, implementing federated technology and open source solutions and systematically assessing dependence on single points of failure and U.S. big tech. That requires making sure we have the necessary in-house specialists to do that, or start hiring and training them in earnest. All this is easier said than done, but these are priorities in a world that is changing fast and erratically.

References

- Dear Donald Trump: A letter from Nature on how to make science thrive. (2025). Nature, 637(8046), 517–517. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00050-1

- Basilio, H. (2025). ‘We are a target’: Scientific society under pressure after Trump DEI crackdown. Nature, d41586-025-00372–0. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00372-0

- Protecting Science in Times of Crisis. (2024). International Science Council. https://doi.org/10.24948/2024.01

- The Lancet. (2025). Supporting medical science in the USA. The Lancet, 405(10488), 1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)00814-1

- Chugh, M., & Coates, J. (2025, February 12). Science is Under Siege: The Open Science Community Must Act and Lead by Example. Upstream. https://doi.org/10.54900/eher5-hdf87

Jeroen Bosman is open science policy advisor at Utrecht University Library in The Netherlands and Jeroen Sondervan is Programme leader open scholarly communication at Open Science NL.

Copyright © 2025 Jeroen Bosman, Jeroen Sondervan. Distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.